Restoration of degraded Hong Kong coral habitats using multiple active coral restoration approaches

Funded by: PEW Fellowship in Marine Conservation, Environmental and Conservation Fund (listed in no particular order)

Coral reefs around the world are in dramatic decline in the face of climate change and anthropogenic disturbances. Currently, most efforts in reef restoration have focused on using asexual propagation of coral, i.e. fragmentation of source colonies for transplantation. This approach relies heavily on the availability of existing corals from the natural environment and is limited by genetic diversity of the source colonies. Taking advantage of the high fecundity of most corals, sexual propagation approach has negligible damage to source colonies and offers the promise of greater genetic diversity of the transplanted coral colonies that is likely to improve the adaptive potential of these corals to future disturbance. This study utilizes multiple active coral restoration approaches for coral restoration in Tolo Harbour and Channel in northeastern Hong Kong, including sexual and asexual coral propagation, ex-situ coral nursery, and larval enhancement technique, in degraded coral areas to mitigate population declines of corals, enhance biodiversity, and promote reef resilience to cope with future climate change. This will be the first time that multiple active coral restoration strategies will be employed in Hong Kong to serve as a foundation for larger-scale restoration efforts in the future.

The Lab Nursery at the Simon F. S. Li Marine Science Laboratory, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. © Coral Academy

Background

The Tolo Harbour and Channel is a sheltered harbour located in the north-eastern New Territories of Hong Kong. Its topographical features provide an enclosed and protective environment that once harboured more than 30 coral species with high coral coverage. Nonetheless, the urban reclamation along the inner harbour coupled with the booming human population residing nearby in the 1980s have enormously devastated the marine environment and ecosystems.

The drastic rise in anthropogenic activities, involving agriculture, piggery, and industry, unavoidably led to a tremendous increase in the production of organic sewage being discharged into the water stream. As a result, the excessive nutrient levels in waters formed a pollution gradient, rendering frequent occurrence of eutrophication and algal bloom. As this tragic incident has been infamously known as Hong Kong’s first marine ecological disaster, the local government decided to take progressive action to address the heavy water pollution problem caused by ineffectual wastewater treatment.

Despite the significant improvement of water quality followed by the implementation of the Tolo Harbour Action Plan (THAP) in 1987, there have been no signs of natural recovery of coral. In the current time frame, it shows that natural recruitment of coral is necessary, but is not sufficient to restore the damaged coral communities. An active restoration plan using transplants may therefore be needed.

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

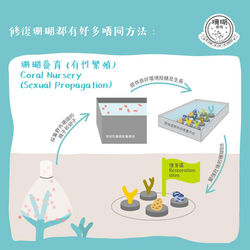

Restoring Coral Communities to Meet a Changing Climate

Currently, most efforts in reef restoration have focused on using asexual propagation of coral, e.g., corals of opportunity, defined as detached living hard coral fragments on sea bottom that have a poor chance of survival in the field. By collecting, cutting, and culturing these fragments in lab-based or field-based coral nurseries, we are preserving the existing coral biodiversity and these coral fragments could serve as a seed stock in restoration exercises. This approach, however, relies heavily on the availability of existing coral fragments from natural environments, and is limited by genetic diversity of the source fragments. Sexual propagation techniques involve the collection of egg bundles from corals during coral spawning, allowing them to fertilize and develop into larvae/juveniles before re-introducing them back to the degraded sites. Taking advantage of the high fecundity of most corals, this approach has negligible damage to source colonies and offers the promise of greater genetic diversity of the transplanted coral colonies that is likely to improve the adaptive potential of these corals from future disturbance.

Using both asexual and sexual coral propagation approaches to assist restoration of Hong Kong Coral Communities. © Coral Academy

Restoration in Action!

Asexually Propagated Corals (Fragments)

In 2019, our research team out-planted around 200 coral fragments in the Bush Reef and the Knob Reef on natural substratum in Tolo Channel for the purpose of coral restoration and monitoring at an experimental scale. Five genera of coral, originating from corals of opportunity, including one branching genus (i.e. Acropora) and four massive/submassive genera (i.e. Platygyra, Porites, Leptastrea and Cyphastrea) were used (see photographs below).

On-going post-outplant monitoring has shown these outplants to have high survivorship (~ 90%), positive growth, and they eventually became homes for other marine organisms including seahorses.

Out-planted Coral Fragments (from Left to Right), including Acropora, Platygyra, Porites, Leptastrea, and Cyphastrea. © Coral Academy

Corals Out-planted onto the Natural Sea Floor at Knob Reef. © Coral Academy

Out-planted Coral Fragments with a Seahorse (Left) and Butterflyfish (Right) Sheltering Nearby. © Coral Academy

Sexually Propagated Corals (Baby Corals)

In addition to the use of asexually propagated corals, our team also carried out a preliminary scale study in 2019-2020 using sexually propagated juveniles of Acropora pruinosa corals for out-planting. These juvenile corals had been cultured in the coral nursery at the Simon F. S. Li Marine Science Laboratory, CUHK, until they reached the size of 2 cm and were then out-planted in 2019. Subsequent post-outplant monitoring revealed these corals to have high survivorship (88%) and positive growth.

Farming sexually propagated corals in Marine Science Laboratory, CUHK (a) Spawning of Acropora tumida and Platygyra acuta. (b) Planula larva and spat. (c) 6 months old A. tumida baby coral (d) Students culturing coral embryos. (e) 2 years old coral juveniles in the culturing facility. © Coral Academy

Acropora pruinosa coral (from Left to Right) 2 days old baby coral, 2 years old juvenile and out-planted juvenile in Knob reef, Tolo Channel. © Coral Academy

Secondary School Students are Helping to Restore Our Local Coral Communities

Since 2019, Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department and our team have been co-organising the Coral Nursery Education Programme. Apart from learning about the biodiversity and importance of Hong Kong’s coral communities, secondary school students joining the Programme are engaged in taking care of local coral juveniles and fragments, placing them at the frontline of marine conservation work and contributing directly to local coral restoration.

Coral Nursery Education Programme 2020-2021 Programme highlight © Coral Academy